The Emperor's New Clothes?

As if by magic The Strokes arrived from New York, stirred up a fashion

press frenzy and kicked their way into the British charts. The hype had

nothing to do with us," the "coolest band on the planet tell Bob Gordon.

Photography by Toni Wilkinson.

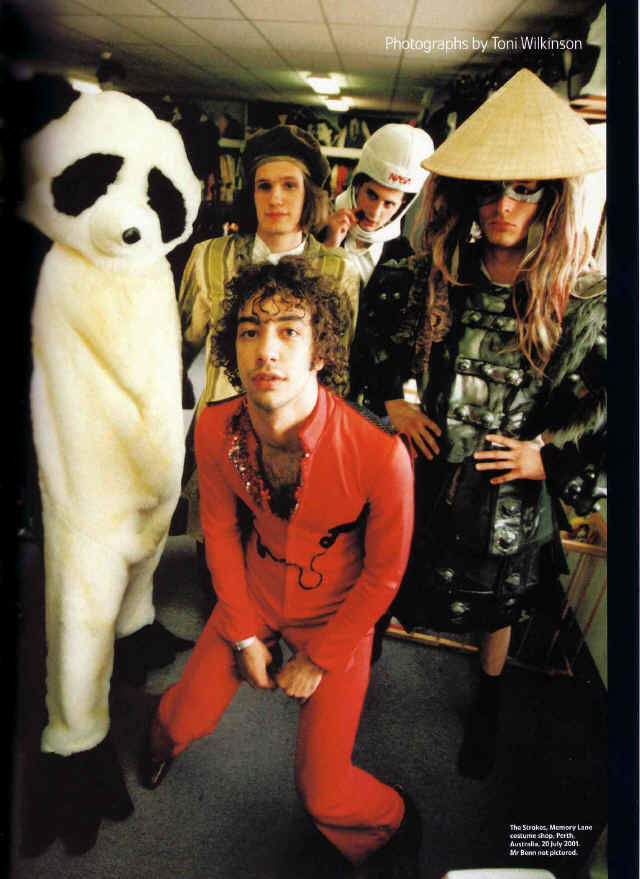

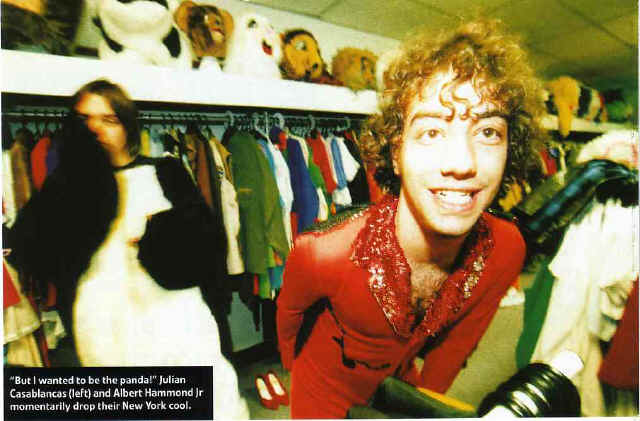

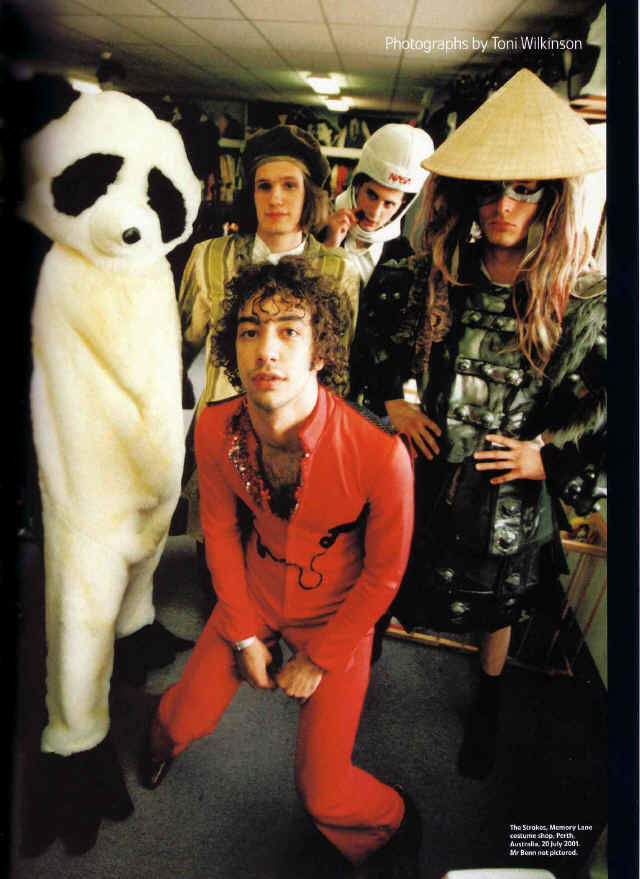

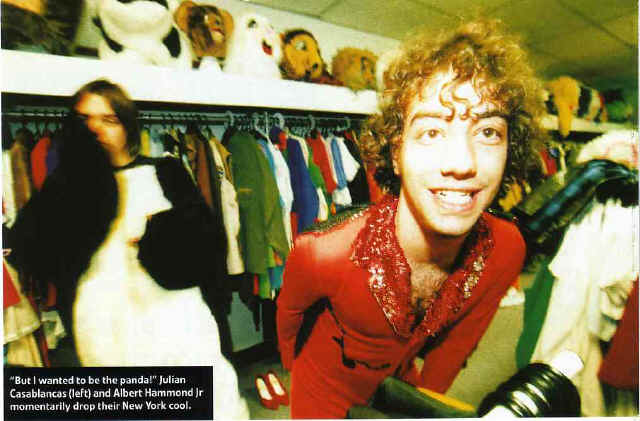

Julian Casablancas looks like he's woken up in Disneyland. A little hungover after a show the night before, perhaps, but the treats on offer at Perth'.s Memory Lane costume store have got him on the good foot.

Shuffling around in a white '40s sports jacket, an oversized black tie and a pair of obviously beloved torn jeans, the vocalist and his band have been taken on a shopping expedition by You Am I, the big-noise Australian group they're supporting on tour.

"Man, this is the best clothes shop I've been to in my life!"

He's probably seen a few. Infamously his father is John Casablancas, founder of New York's Elite Modelling Agency.

But with suits and ties at one end of the store and chicken outfits at

the other, one can't imagine him normally shopping in a place like this.

"I'd shop in a thrift store, but this isn't like a thrift store.

It's is like ... a Hollywood costume studio."

Unsurprisingly, the rest of The Strokes agree with him. As they paw

through the racks, toying with the bizarre fancy dress apparel on offer,

their wallets are out for that impossibly old-cool attire that you can

only find in a place like this.

Guitarist Nick Valensi emerges decked out in a samurai outfit that looks as if its been

borrowed by the rat oil the cover of the last Leftfield LP. "Don't

make fun of my nobbly knees," he pleads, brandishing a sword.

An elderly Robin and Maid Marion shopping in the store, in possibly their first ever encounter

with a New York rock band in a costume shop, avoid eye contact with the

lower half of his body. "Wow," says Nick. "You guys look great. No, really."

The Strokes maybe the coolest band in the world, but not at this moment. While their bags are stuffed with rockworthy apparel (guitarist

Albert Hammond

Jr has already purchased four pairs of shoes, including Cuban heel boots and a pair of "Dutch Chocolates", plus a grey pin-striped suite he'll wear at tonight's show) the men themselves look like they've been cast in a pantomime.

Resplendent in a panda outfit, Casablancas surveys the red Elvis-suited Hammond

Jr. "You're dressed like Elvis but built like David Bowie." he laughs,

as bassist Nickolai Fraiture walks up looking like Henry VIII.

Temporary drummer Matteo Romano (filling in for Fab Moretti, who is

nursing a broken hand in New York), inexpicably combines the gangster

look with NASA headwera. You Am I frontman Tim Rogers, tour manager

Kevin O'Dwyer and the band soundman James giggle from the wings as a

nervous shop assistant steps forth.

"Umm... I assume that all you guys are together?"

The Strokes have all been together, in one way or another, since 1995. The band itself were a way off from forming, but as Casablancas laughingly puts it, ',the magic began" when, as a 15-year-old, he met Valensi, who was two years his junior. Both attended New York's Drake School, a private institution where hip hop was high on the schoolyard musical agenda and skinny white boy rock was, well, lower.

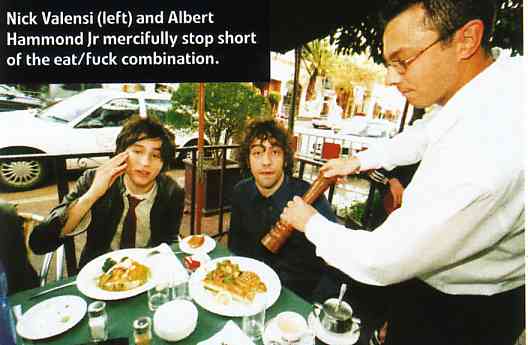

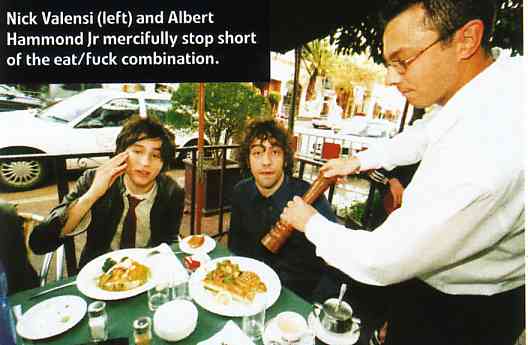

Enjoying an al fresco lunch in Perth's nightclub strict Northbridge, The Strokes are a laconic collection of people, but incredibly affable when the mood takes them. When asked if they'd like the Q tape recorder turned off during the meal, Valensi leaves us agog with his willingness to

cooperate: "We'll do whatever you want, man. We can talk while we eat. We can talk while we shit. We can eat while we fuck!"

A photo request for the latter is politely declined, but the mood is up, even as an uninvited street character attaches himself to the party. On the periphery of the interview there is a constant mumbling, and it's not until later that we learn that, as

the Strokes reminisce, he has asked the Q photographer if he can sit in her lap because, apparently, he as a spaceship that can take us to Alice Springs.

Meanwhile, the band seem to enjoy digging back through their history.

"I thought it'd be cool to be a modern-day composer but I didn't know what the hell music was all about," Casablancas reflects. "Nick had played he guitar since he was, like, six. And I did not. I met this bloke who played the guitar really well and I was blown away."

"Julian caught on really quickly," Valensi adds. It took one guitar lesson, he didn't even know any chords or anything and was writing songs on, like, one string. It was like wow. It was impressive to see

someone pick up things so quickly. Then he just went way over my head."

Before long the pair had enlisted fellow student Moretti (the absent Stroke) on drums and Casablancas's best friend, Fraiture (the, erm, quiet Stroke) on bass. There was a missing link, however, which could only be filled by another guitarist. It was a recruit that didn't appear to be "falling out of the sky" until one was found under curious circumstances.

He came, instead, from Switzerland, via Los Angeles. Casablancas had met him at Swiss Rose School in 1993, when both were the only American students. "What was I doing in Switzerland?" he asks. "I wish I knew. My dad had gone there and his parents were from Europe. So I went and... I don't know if it was a good

idea."

For his part, Hammond Jr (Hammond Sr sang the '72 US hit, It Never Rains In Southern California) didn't know just what the hell he was doing there either, but when his Los Angeles-based family moved to New York in 1999 he immediately looked up Casablancas. Swiss time had finally paid off and The Strokes, so called simply because "it was something we agreed on", were five.

"Our goals then were, like, real small," Hanunond Jr recalls. "To be able to play a song and finish it and end. I'm serious. We couldn't do it. Most people join a band and it's like, OK guys, rise to fame. For us it was just that we liked music and liked playing songs. When we started, all of us together, it was fun."

It's the fun and friendship within The Strokes that leaves them wondering why so many make such a big deal out of everyday things. They're close enough to each other to air grievances constantly and immediately as friends do, but have gained quite a reputation for fighting among themselves and with others.

"The shit that we fight about is usually pretty small shit," Hammond Jr contends. "I think the key to arguments is to not hold grudges. Once everybody's point has been heard it's like, Alright, I'm not gonna hate you for the fact that you don't like my

fucking sneakers."

"The important issues we tend to agree on," says Valensi. "It's usually the irrelevant things that we argue about, that don't make any difference. Would you agree Julian?"

"Yeah. It's true," Casablancas allows, clearly uninterested in the subject.

In early 2000, The Strokes played their first gig at "the shittiest club in New York", the now defunct Spiral. It was a Tuesday night and more people were on the stage than the audience. Across the street was their dream gig, the Mercury Lounge, the coolest small band venue in New York. They gigged constantly, progressing to other venues such as The Acme, Baby Jupiter and Arlene Grocery, before landing in the Mercury Lounge and claiming the venue's manager, Ryan Gentles, as their own. Already The Strokes stood out, even on their home turf. In a scene rife with cool schtick, the band were simply being themselves.

"There really is no 'scene' in New York," Valensi says. "For us at least. A lot of bands like to tweak their gimmick, like become mod or something, and get into that scene. We just try to avoid that and get everyone to come and see us."

"At the beginning of 2001 we were one of a handful of really popular bands in New York. We were taking big baby steps to get to that point. It was like, If we can get to be a really popular band in New York that means we're good. And we can do it anywhere else."

What happened next, happened quickly. Gentles had sent a copy of the band's demo tape (of The Modern Age) to Rough Trade honcho Geoff Travis in London, who loved it. To the gobsmacked wonder of the band, Gentles told them over dinner in New York that Rough Trade not only wanted to release The Modern Age as a single, but fly them to England. Popular musical myth claims Travis offered them a record deal halfway through the first listen of the demo's title track.

Hip had met hype and The Strokes, who had just finished recording their debut LP in New York, were the catalyst. With their first UK visit whipping up a media storm, they returned in June with fellow NY protagonists the Moldy Peaches for a sold-out 16-date run, in support of a second single, Hard To Explain/NYC Cops. Platitudes came from all around and the band seemingly usurped their New York popularity once the release notched up a place in the Top 20.

With notoriety came the prerequisite celebrity attendance at shows. Radiohead and Kate Moss showed up to see the band's gig in Oxford. Notable others also flocked to the show at London's Heaven nightclub. The fashion press was equally excited.

"Kate Moss?" enquires Casablancas. "She was talking to [Moldy Peaches vocalist] Adam Green' "

"She knows we're gay," Hammond Jr laughs.

"If celebrities wanna come to our show I just hope they're coming cos they like our music," Valensi says, earnestly, "not because it happens to be the cool place to be that night. Kate Moss is a person just like the dude in the front row last night who

I don't even know. Just as long as people are coming because they like our music, it's the right reason to go to a show."

Apparently some people who were going for the right reason ended up paying up to £180 for the privilege.

"That's true," says a cringing Casablancas. "That's really embarrassing. It's so ridiculous.

I think if somebody paid that much money for the show it definitely would not be worth it."

"If Kate Moss paid that, it's alright," says Valensi.

"Actually, on the night of the London Heaven show we had an after-party and this girl told us she paid £50 to get in. So Julian gave her £50."

"I was wasted," says Casablancas, sheepishly. "She was really nice though, you know?"

Do you think the hype may one day damage you?

"The hype had nothing to do with us," says Hammond Jr. "The press made the hype. We should have an interview day with them and ask them, Why did you hype it?"

"I think it's cool if it got our name out to a lot more people," Valensi offers. "If our record was bad then it would be bad, but

I think we made a really strong, cool record. It will overpower anyone saying anything. If it's not true,

I still think we made a great record. [Assumes a Rhett Butler tone] So frankly,

I don't give a shit."

"What happens after our record comes out?" asks Casablancas. "Do we, like, get jobs again?"

"No," says Valensi, with feeling. "Hey! What are you doing, man?"

Perhaps intoxicated by the presence of skinny rock boys with New York accents, the Northbridge street guy suddenly makes himself comfortable in a vacant seat between Q and Hammond Jr. "Why are you sitting down man?" the guitarist demands. "We didn't invite you."

The interloper, rising to his feet, is a little miffed "Don't fly too high," he hisses, eyeing Valensi and Hammond Jr. He backs off several feet, then stands his ground, mumbling inaudible threats. After politely enquiring if our

mystery guest would like to move on, the band's soundman, James, apparently the owner of a black belt, rises to his feet and towers over the interloper, demanding his departure. The whiff of potential violence is in the air.

"Is this recording?" ask the band collectively pointing to the tape recorder.

"That guy's scared shitless, man," says Hammond Jr gleefully.

"James could, like, seriously kill that guy with his finger," Valensi claims.

Outsized and obviously outclassed, the interloper cuts a hasty retreat, as James takes his scat neither proud nor perturbed by the stand-off.

So then, how do you like the locals?

"In New York every third person's acting like that," Casablancas says. "Hardly anyone acts like that

here, so when someone does it's even weirder. "

The singer leans back in his chair, laughing quietly at the interruption.

"James! I'd hate to fuck with you, dude."

Later that night, at the Globe Theatre in Perth, The Strokes have just played to a hugely enthusiastic Friday night audience, opening for Australian rock

icons You Am I.

While the previous night' performance was alcohol-driven in the best sense tonight's set is a heads-down, rock-sure outing. It's immediate and somewhat magic and it's not lost on the crowd, who aside from perhaps hearing The Modern Age on the national youth radio network, Triple J, know very little about the band.

Casablancas and Hammond Jr are hot-to-trot in their more sensible fashion purchases for the day. The singer leans on the mic, detached yet demonstrative. Hammond Jr wears his guitar way too high. Valensi is all style at stage right, while Romano drums astutely, given his temporary role. Bassist Fraiture, the quiet Stroke, is steady as ever.

Q, accepting an enthusiastic proposal by the band to continue the interview post-gig, evades several unimpressed security guards, bounding backstage to help glow in the glory of a gig well played. Oddly, the mood is mixed, the band stretched out on loungers, sipping on Coronas. They're obviously too tired to talk it up, though Hammond Jr, despite a more immediate problem, is forthcoming.

"Sorry dude. The zip's broken on my fucking pants."

As Hammond Jr rues his broken fly, he talks of the constant comparisons his band endures. There's a sense that The Strokes may be embedded in something of a New York City tradition, but decades on from the likes of the Velvet Underground and Television, their 21 st century experience is understandably their own.

"It took us a year and a half to find our own sound," says the guitarist. "We like so much stuff. If you go to a record store you'll find our CD in the rock or pop category. But the music is more worldly than that, just because of the way we think."

"The best thing to say about how we sound is to say, Go check them out." he adds. " If the person in the band can't even describe what we sound like, then how the hell are you gonna do it?"

|